Art of the 20th Century

Mac Conner

Illustrator extraordinaire

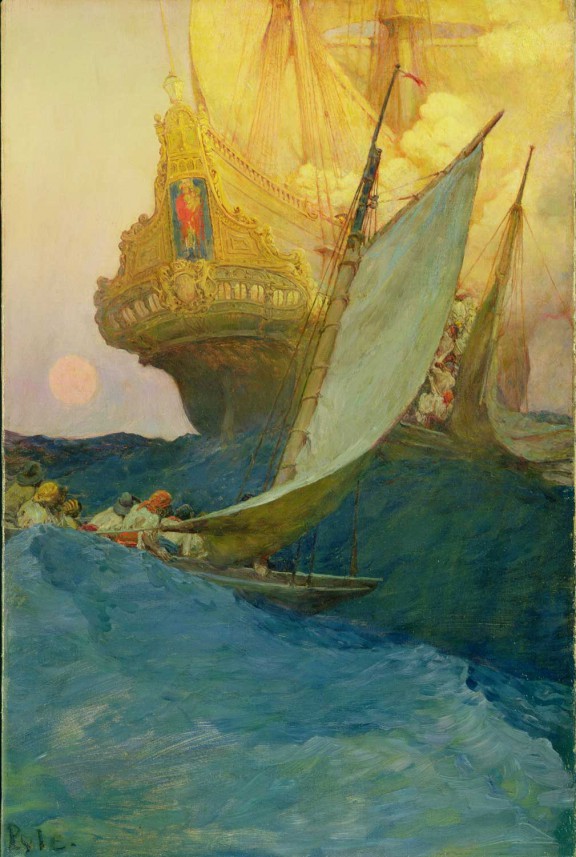

I have always admired the American illustrators of the early to mid 20th century. N. C. Wyeth, father to Andrew Wyeth and grandfather to Jamie Wyeth, made so many fanciful illustrations from pirates to English knights. Gloriously colored and carefully designed, his pictures were meant to pique the imagination and churn the spirit. Wyeth, like many of the illustrators, proliferated a considerable number of works (around 5000!) due to the popularity of color print media during the century.

I remember in art school mentioning N. C. Wyeth to one of my professors. He taught painting of some sort. I don’t remember in what area. His dismissive attitude when it came to illustrators struck me as more than just harsh, but entirely unwarranted. The American illustrators of the early to mid-century possessed amazing talent. Not only could they design a picture to present exactly what they wanted to say, but to also do so in a short amount of time. They were always up against a deadline and supremely enjoyed what they were doing. If even one percent of my professor’s class possessed the ability of illustrators like Rockwell, Wyeth or Parrish, he would still not recognize any degree of sophistication. Even today, many who think themselves elite, find an artificial definition between art meant for utilitarian purposes and work meant for the glitterati and the inner circle of the art world.

I suppose the most influential reason for rejection by elitists in the art community, besides the appeal to the broad public, came from the range of emotional states in many illustrations. Not only did the illustrators portray serious subjects, but they examined the humorous and lighthearted moments in everyday lives and, worse yet, they did it for capitalists in an effort to provide the public with what they wanted. It doesn’t matter that modern art owes a large debt to the patronage of extremely wealthy capitalists such as Guggenheim and Saachi. The sanction of those with vast quantities of money seems to mitigate the hypocrisy. More importantly, they had to convey ideas as directly or succinctly as possible and they were incredibly good at doing so.

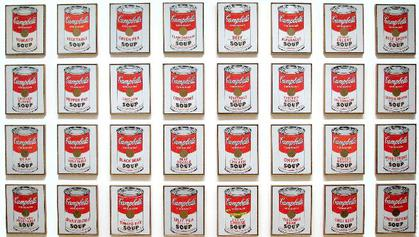

How is the above work any more expressive or valuable than the above works by illustrators. Truth is it’s not. Indeed, one can make an argument that the Warhol work shows little thought and required little skill to produce. Art epitomizes subjectivity to the point that one can really make any argument or admire anything. Since the time of the beginning of the 20th century, art has become detached from ability, intellectual prowess or talent. Celebrity consumes the entire art world elite these days. This is why in reading art news, we hear of some current pop sensation attending an art show or buying a work of art, or we hear of some television actor hobnobbing with the latest, fabulous artist. This artist might pickle a shark or can excrement or some other silly, if not embarrassing thing. Just as with any other celebrity, It really doesn’t matter. Intolerance, however, rears its ugliness among the art world elite.

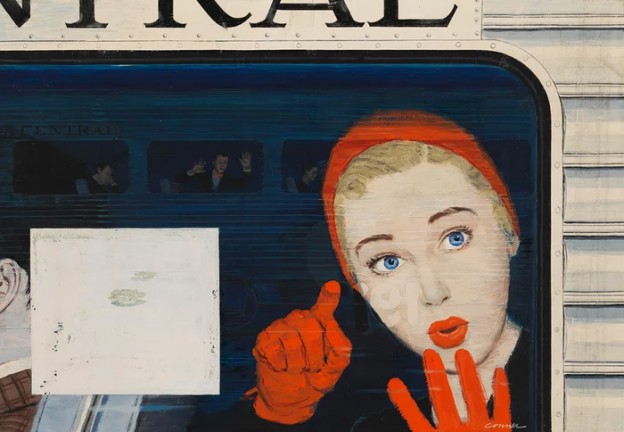

Now we come to Mac Conner. Conner entered the vibrant world of New York working illustrating Navy training manuals. He was in the right place at the right time due to the vibrant commercial activity after the World War. The demand for illustrations for publications and advertisements was enormous. In 1952 he set up a studio with Bill Neely and Wilson Scruggs called Neely Associates and his career skyrocketed.

For a little information and a video with the artist speaking about his work, check out this link.

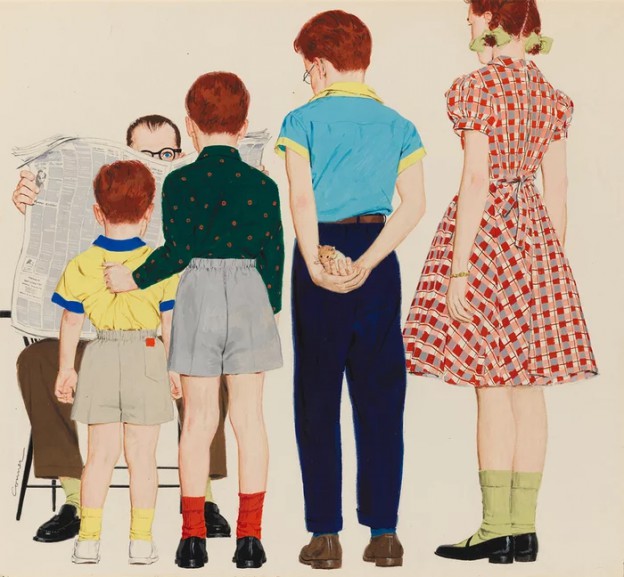

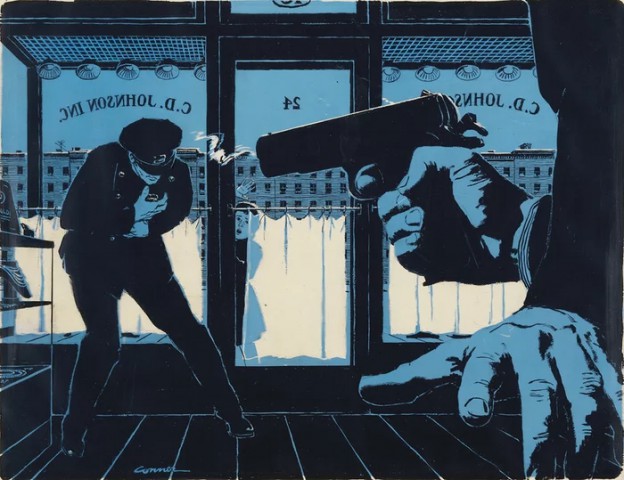

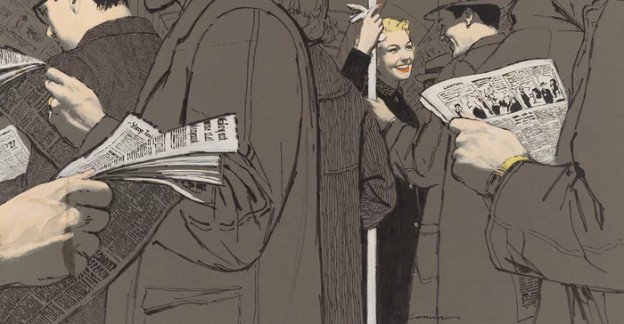

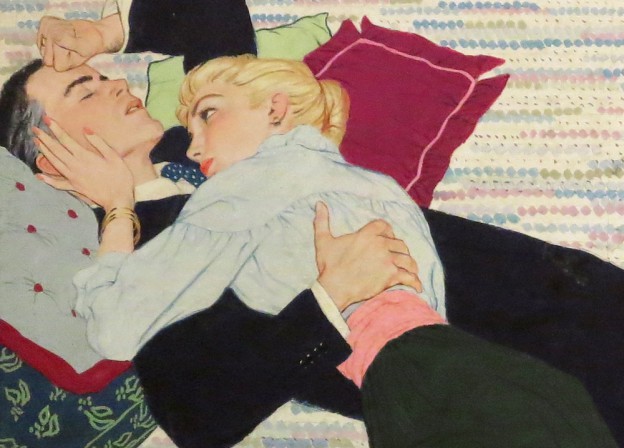

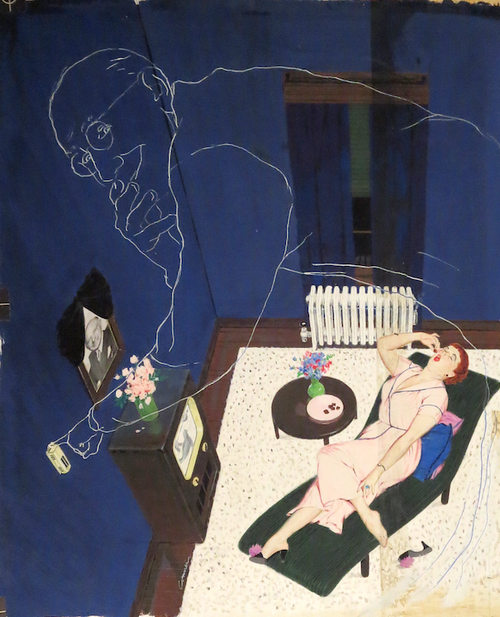

Conner grew up admiring the Saturday Evening Post front covers. Claiming he never considered himself an artist, just someone who liked creating pictures, his images appear influenced more by artists like Degas or Toulouse-Lautrec than by Rockwell. He conceives unusual perspectives and captures fleeting moments with strong angular designs or framing activity with expressive foreground figures or inanimate objects. The previous picture contains a private moment in a fire-escape cage as we spy on the couple from above. We have all sorts of mixed feelings being at such a height, yet free in the open air. These unusual angles and inventive compositions gives such delight in viewing, emphasized by a strong graphic rendering.

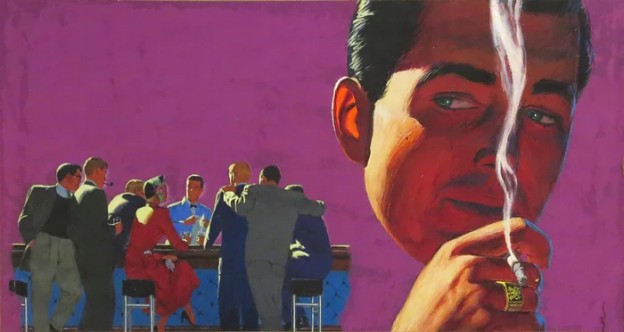

The above amazing image exemplifies Connor’s artistic sensibilities. Here, he placed a purple, foreshortened bicycle pointing out toward the viewer, then frames the couple and basket with the handlebars, the basket with the pedal and the wheel of the other bicycle. How awkward a composition in another’s hand. The picture follows a horizontal rhythm across the illustration and uses the woman’s and the man’s arms to enclose her pleased and satisfied look. The slight turn of the handlebars and the visual line of the man’s leg, draws our vision to further accentuate the focus of this picture. I could go on… The delightful design of this work does not require background or grass. One can easily forget how “incomplete” the image is.

I can not describe enough how pleasing Mac Conner’s pictures are to me. His graphic style, his compositional invention, his use of color and detail, his clever expressions of a moment in time, draws my interest time and time again. Would I prefer to have a Conner over a more well-known artist of the 20th century? (Forget that large sums of money would be involved.) Honestly, I would. Maybe someone else might also come to this conclusion.

For further viewing:

“The Original Mad Man of Advertising: Mac Conner”.

“Mac Conner: A New York Life”.

| Mac Conner Illustrator |

HBosler

You must log in to post a comment.